Q&A: Governance

What new board members need to learn in their first 100 days

By:

Kristi Garrett

Running for your local school board is a tremendous commitment, but that’s nothing compared with the learning curve that happens once you take the oath of office.

To help new trustees get off to a good start, California Schools writer Kristi Garrett sat down with two of CSBA’s governance consultants, Leslie DeMersseman and Luan Burman Rivera—both past CSBA presidents—to find out what their experience shows to be the most crucial skills for new board members.

What do new board members need to know about becoming an effective trustee?

LESLIE: To me, the hardest thing for new board members is recognizing that they have joined a body that has collective authority—that, as an individual, they have no authority. Anything that they would like to see happen, they have to work through with the rest of their board. All decisions are made by the collective body, not by individual trustees.

New board members, in particular, have a need to feel like they’re doing something. Generally, people who are elected to school boards are doers and problem solvers; that is why they are inspired to run and why people elect them. So when people come to them—whether it’s staff or a community member or whomever—with their problems, a new board member feels like they’ve got to do something about it; they want to fix things and they have no authority to do that. In fact, they’re probably stepping all over their board policies in trying to fix somebody’s problem, because there is someone on staff who is responsible for resolving that issue.

So if a community member comes up to them in the grocery store, or perhaps a parent sees them on a campus and approaches them with a concern—what should a board member do with that?

LESLIE: Board members do have to be accessible to the community. They can’t just say, ‘I can’t deal with that, I’m a board member and we don’t do that. We have collective responsibility.’ They’ve got to listen to be sure they understand, and they’ve got to try to be an empathetic listener. But then the board member needs to send the person back into the system at the most appropriate place.

So if it’s a parent who’s concerned about the teacher, then you ask them: ‘Have you spoken to the teacher? It might be very helpful for you to go in and listen to the teacher or share the concern and hear what the teacher has to say. Then, if you’re not happy, you should go to the principal.’

It’s even more important with staff. By law, there are lines of authority and chains of command in school districts that the staff has to follow. A board member who gets into the middle of that—especially if they start taking sides among staff members— is violating somebody’s rights. That can turn into a litigious issue.

LUAN: Also, when board members hear concerns out in the community, they need to let the superintendent know that there are issues brewing so the superintendent is informed and can respond appropriately.

LESLIE: Yes, the superintendent can look into an issue, but it’s not up to board members to do research and dig around trying to figure out what is going on. That is what they hire staff to do.

What does a new board member need to know about the Open Meeting Act, or the Brown Act?

LESLIE: I think probably the hardest thing is that, by law, they are not to engage with the public on any item that is not on the agenda. The point of the public comment period is for the public to give input on a subject that is not on the agenda. Sometimes, new board members in particular want to engage—have a dialogue—after the person has made their comment, to have a discussion with them.

LUAN: There’s this tendency to feel uncomfortable because someone has come and shared with us, and now we can’t respond to them? It just feels unnatural and weird to people.

But the point of the Brown Act is to protect the public’s right to know. All of the board’s work is done in public, except for closed session items.

The reason the board cannot discuss a topic that is raised in public comment is because that item was not on the agenda. Therefore, the rest of the community was not aware that that particular item would be discussed at the meeting. So if you discuss that topic, you are really violating the rights of the rest of your community.

The item might be placed on an agenda at a later date, or perhaps it is something that will be handled administratively. There are a number of ways to resolve issues, but items cannot be discussed that evening if they are not agendized.

Why is that important?

LUAN: Because if you start engaging a member of the public in a debate and deliberation about a topic, then you’ve elevated somebody to the board table who has not been elected. The board is conducting its meeting in public; it is not a community forum, it is not a town hall meeting. It is the board doing its work in public. The board is informed by public comment, but the deliberation takes place between the board members. The board is the elected authority that is entrusted with the responsibility to deliberate and make those decisions.

School finance is such a complex, convoluted body of knowledge, how can a new trustee begin to get up to speed?

LESLIE: I think one of the confusing things for a brand new board member—if they were elected in November—is that in December they will likely have to approve their district’s audit at their very first meeting, and they’re also required by law to approve the first interim financial report. So right off the bat, before they’ve had any background on that at all, they’re taking those actions because of the legally required timelines.

A great place to start learning about finance, then, is at their first CSBA Annual Conference, where they can attend the Orientation for New Board Members, and in January there’s the Institute for New and First-term Board Members that covers finance in greater detail.

LUAN: And of course there’s an entire module on finance in the Masters in Governance curriculum.

LESLIE: And we always get some good information from the experts during our Forecast Webcast in January. So there’s help to be had.

I think in the meantime, though, it’s a perfectly good question to ask the superintendent: How can I as a new board member get up to speed? Do we have an orientation? If it’s not offered, new board members need to ask to be oriented on finances, or curriculum, or facilities—whatever big things are happening in the district.

We really stress the importance of having a new board member orientation. My preference is that they do that as an entire board, with the superintendent. Maybe it’s about facilities or Program Improvement; ask ‘How do I learn about all that? How do I know what that means?’ They are learning a second language. And they should be strong enough, when somebody’s using an acronym, to say ‘would you help me remember what that means?’

LUAN: If the new board member does not understand the meaning of an acronym, then the odds are that members of the audience do not understand it either.

So are those orientations formal, noticed meetings?

LESLIE: Yes, everything is noticed. The only way they wouldn’t be is if the meeting included less than a quorum and is not part of a serial meeting, where the same subject is discussed with other board members in some combination that adds up to a quorum.

LUAN: An orientation session is hugely important, but then new board members should also know that they can go back to the superintendent and ask their questions. Perhaps the superintendent will recommend that they need to get more financial information, and therefore spend more time with the chief business official. Or if they want to know more about curriculum, they should see the person who is in charge of curriculum and instruction in the district. New board members should get an idea of who is in charge of these different programs and where they can get additional information.

So is the study session, or orientation session, a good way for a new board member to learn about the district’s operations? Also, what do board members need to know about the students in their district?

LESLIE: They need to know what their student demographics are. They need to know how many schools they have. They need to know the names of the key people in the district, whether they’re administrative staff, maintenance staff or principals, etc. Who are the board officers and what are their roles? How to reach the people you need to reach.

And the preferred methods for doing that?

LUAN: Right.

LESLIE: I think there’s another issue new board members need to be aware of. Maybe I ran for the board because I didn’t think we were doing the best job we could for our GATE students. So the question to ask is, ‘How can I bring up that interest?’

When I was on the board both of my kids were involved in drama. The head of the drama department and the band director put on a musical every year. Then they put on student productions and did competitions where they went out to other schools. It was really an award-winning program. They were putting in many, many more hours than any of our sports coaches, yet the stipends were much smaller.

So I went to Bill, our superintendent, and said this didn’t seem fair to me. I didn’t want to rant and rave at the board meeting because everybody knew my kids were in drama. So how could I approach this so that it was looked at in comparison to other stipends? I didn’t want to become the person who is advocating only for this one group. Bill suggested that I ask, ‘What is our process for deciding what the stipend is for the various extracurricular activities that our staff is participating in? And how can we make sure that our stipends are fair and equitable for all of our extracurricular activities and for the staff participating in them?’

So it’s getting at the policy level question. Whatever your interest is, you’ve got to try to make sure that there’s fairness and equity through the policies you have in place.

LUAN: So it’s balancing all of these different aspects of your decision making: Serving all the kids, working together as a team, responding to all your different constituent groups, and balancing in your own beliefs and values. Not losing those beliefs and values, but balancing them into all these other factors.

LESLIE: This is perfect for this conversation. Because the new board member has no idea …

… Of how to balance their own beliefs and values—which is why they ran and maybe had a great deal to do with why they were elected—with the board’s overall responsibilities?

LESLIE: Right, and with their legal responsibilities. Their own beliefs and values are not at the top of that list. But what’s the most important thing you have to do? It’s making sure that every child in the district has the very best opportunity that you can provide. That really is what our public education system is about.

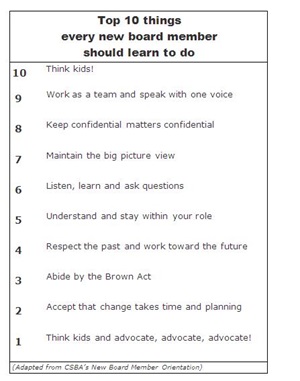

Some of your consulting materials mention working as a team, speaking with one voice, and collective responsibility. Can you expand on what that means?

LESLIE: That’s hard, the speaking with one voice. If I’m a new board member and that evening I just lost a vote four to one and the media meets me out in the hall asking, ‘What happened?’ I could say, ‘The rest of the board just doesn’t get it. I’m voting like my constituency wants me to.’

LUAN: That’s a really important point, because I’ve heard so many people say, ‘My constituents want… ’ Well, who are your constituents? There are people who elected you, but once you’re on the board, you’re serving all of the children in your community. You’re not serving a constituent group anymore. Making that shift is important.

LESLIE: And that principle also means standing behind the board’s decision. Your responsibility is to deliberate at the board table, and then once the vote is taken, you stand behind that. You don’t have to be the main cheerleader, but the answer to the reporter’s question is: ‘You know, we had a really good discussion, I made my points as hard as I could, but the board voted and this is the direction we’re going.’ Because otherwise it throws the district into mass confusion.

I’ve also heard you say that maintaining confidentiality is an important thing for new board members to recognize.

LESLIE: They’re going to hear things in closed session that cannot be shared. And there are only a few things that can be discussed in closed session.

LUAN: Basically, there are things that cannot be discussed in open session because it would be fiscally irresponsible to do so. In other words, if you’re negotiating a contract with someone, you’re not going to talk about that in open session because it could cost the taxpayers more money. So negotiating a contract, real estate transactions, any personnel issues, private things where privacy rights must be respected and due process followed—basically items protecting the rights of individuals—are all topics that must be discussed in closed session.

LESLIE: Anything where there may be litigation. Now, this is the only part of the Brown Act that has teeth. Any person who violates the confidentiality of closed session, or executive session sometimes it’s called, has actually committed a misdemeanor.

LUAN: There are serious legal consequences if any of that information leaks out. Board members cannot discuss these items with their spouses, their best friends or their cousins down the street. They really can’t talk about those things with anyone else except the people in that room. And that’s a hard one.

Another principle on the list is maintaining the big-picture view—is that regarding the students’ welfare or what?

LESLIE: It’s regarding everything. What we tell the board is, you’re not the doers. You set up the big picture framework. You set up the policies; you create the vision, what it is we want. The big picture view is to see that the district is well run, but not to run it. So it’s putting in place what we want our kids to know and be able to do when they walk out of our doors. Then you say to the staff, ‘How are you going to do that?’ And then the staff does that. But it’s not getting into that nitty-gritty, day-to-day stuff.

You’ve also talked about how new board members need to ask questions. How does understanding the history of the board and the district come into play?

LESLIE: Every two years during elections there’s the potential of having people say and do awful things, and actually cause some damage. For one thing, you may not agree with the decisions that a prior board made. But once you are on a board for a while you understand why that decision was made. You weren’t privy to all the information.

LUAN: I think what Leslie’s saying is really important because I don’t know how many times I’ve heard board members say, I really didn’t agree with this, but now that I’m here and I understand why this decision was made, and it makes sense.

LESLIE: One of the things I love during a Good Beginnings workshop [from CSBA’s Governance Consulting Services] is that by the time you’re done you’ve got charts that go all the way around the room, and it’s all about what they want for their kids. And all of a sudden everybody recognizes that, you know what, we’ve got a lot more in common than not. We may disagree about how we want to get there, but we’re here for the right reasons. And if you understand that, you can get past some of that other stuff and you can have the better conversations.

What other questions should new board members ask?

LUAN: Questions like, how does something get to the agenda? What do I do if have questions before the board meeting? That’s important information for them to have.

LESLIE: Do we have a governance handbook, and what are the bylaws and protocols? Do we have agreements about how we work, and what are they? Can I talk about them? What if I don’t like them?

LUAN: I like to encourage new board members to be patient with themselves. It’s a huge job, there’s so much to learn, and not to feel upset and frustrated. They won’t know everything right away. There’s a huge learning curve there.

As long as they’re committed to doing the work, being prepared and learning the information as they go along, they should feel good about that and just be patient with themselves.

LESLIE: It really is a two-year process. The first year everything is new, and the second year you start having the “aha” moments.

That’s why there’s a whole board and not just one person.

LESLIE: Right.

LUAN: The other thing I would say is that I think learning to listen empathetically is really crucial. The reason there are five or seven people on your board is that all these different perspectives are brought to the table to provide the opportunity for good deliberations to occur. It affords the board the opportunity to come to a good, collective decision that is in the best interests of kids.

But you have to learn to really listen to each other. It’s not good deliberation if I shut down as soon as Leslie starts to talk because Leslie and I ran against each other and I’m mad at her. You have to really learn to listen to everyone and take those perspectives in. You might have an opinion about an issue, but you need to get to where you can listen to other people with an open mind and take in those opinions, as well.

LESLIE: The other thing that I’ve often said to new board members is that most of them have had multiple leadership responsibilities in their lives. Serving on a body with collective authority is unnatural. It’s very hard work. For most people who serve on boards, it’s just not natural.

LUAN: Other than being a parent, it was the biggest growth experience of my life.

LESLIE: Absolutely true.

It’s a humbling experience?

LUAN: Humbling and a big growth experience, too, it’s both. You really learn so much. You learn so much about education, about schools, but you also learn about working with people too. You learn to be flexible when working with people. Because if you really want to make a difference for the children, that’s a crucial skill.

Kristi Garrett ( kgarrett@csba.org ) is a staff writer for California Schools.

LEARN MORE

CSBA offers a variety of trainings, publications and even a comprehensive Masters in Governance program to help school board members fulfill the important role they’ve undertaken—not just in their first 100 days but throughout their public service. Some examples:

Training Opportunities

Institute for New and First-term Board Members: This two-day seminar is held at locations throughout the state each spring. It is one of the best opportunities for newly elected and first-term trustees to learn about their unique role and responsibilities and sharpen their skills in effective governance, finance, human resources and student learning.

The Brown Act: What You Need to Know: Offered in conjunction with the Institute for New and First-term Board Members, this full-day workshop breaks down the complexities of the Ralph M. Brown Act to increase participants’ knowledge of agendas, open meeting laws and use of closed sessions.

Links to the Institute, the Brown Act and other CSBA events—from complimentary webinars and webcasts, offered live as they occur and also archived for easy access anytime, to regional trainings located for easy access throughout the state—are available from CSBA’s Training and Events page found at www.csba.org/Events.aspx. And don’t forget AEC—our Annual Education Conference and Trade Show, coming to San Francisco Nov. 29-Dec. 1. Information: aec.csba.org.

“The Brown Act: School Boards and Open Meeting Laws”

This updated CSBA publication helps school board members understand the intent as well as the letter of laws governing deliberations and actions taken by school board members in board meetings. It’s one of many publications and other products available from CSBA and other sources at the CSBA store.

Masters in Governance program: CSBA’s pioneering governance leadership program that recognizes the necessity for the board and superintendent to work closely toward a common goal. The 60-hour program consists of nine modules which define the roles and responsibilities of school governance teams and provide tools that keep efforts focused on student learning. More information is available at www.csba.org/mig.aspx.